How my dad fishes

for the future

Dive into our changing ocean and

explore how to end overfishing

I love the sea. I love how wild and huge it is. I love how it changes from choppy and stormy to calm and still.

This is me and my dad. He spends his life at sea, and loves it even more than me, because he’s a fisherman.

Hopefully you’ve already watched our film and started to think about how we can make our oceans more sustainable.

Now it’s time to join me and my dad on a new adventure. We’re journeying into the heart of our ocean to explore why we need it, how it’s changing, and what we can all do about it.

Why do we need the ocean?

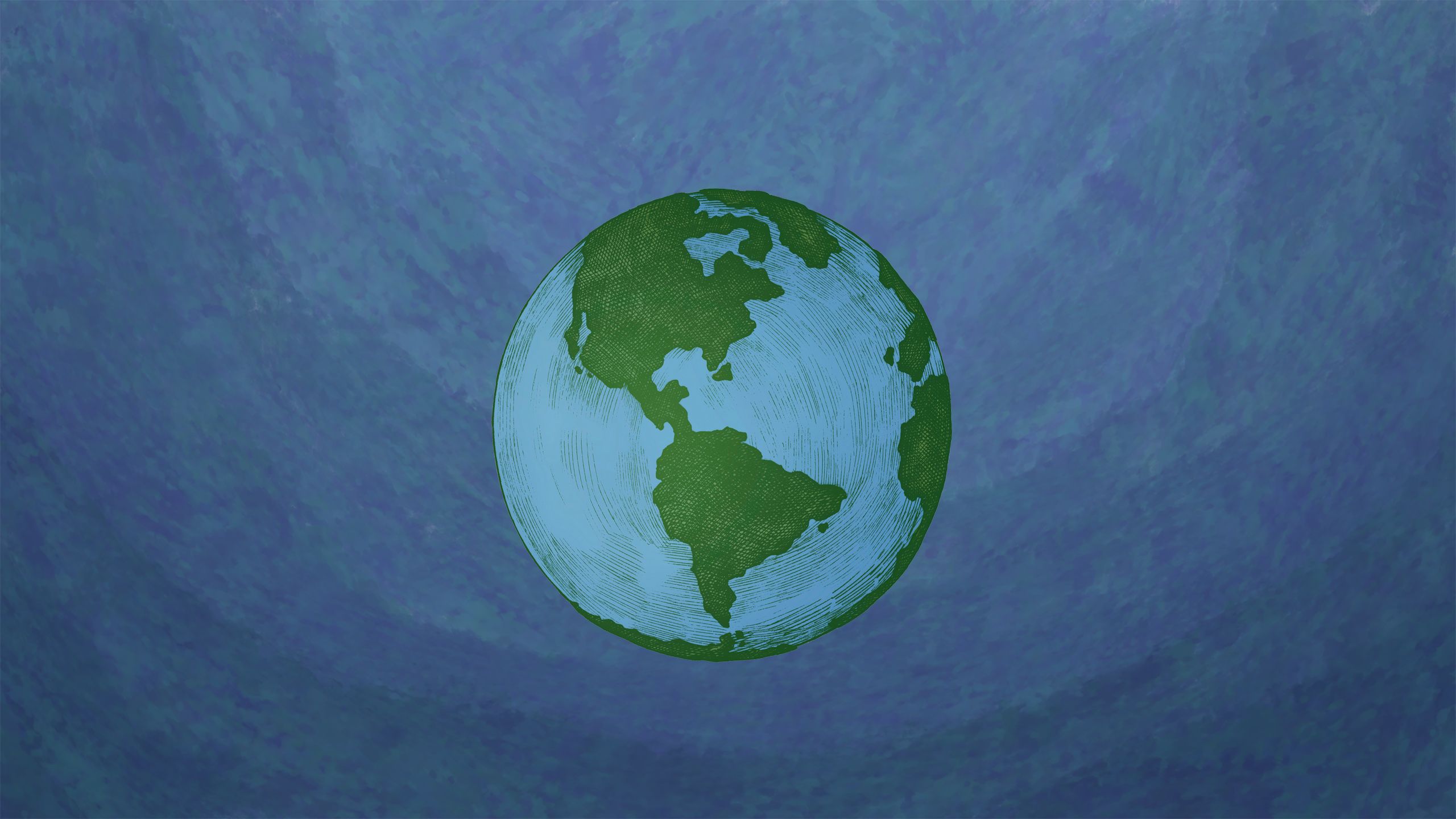

The ocean covers more than 70% of the surface of the earth...

...and supplies half of the oxygen we need to survive

Without it, there can be no life. Without the blue, there is no green.

The ocean is vast

The ocean is so big that most of it remains unexplored. Scientists don’t know exactly how many species of plants and animals live in the ocean, but some think that more than 90% of them have yet to be discovered.

There’s one thing that everyone is agreed on, though: the ocean is home to an extraordinary variety of plants and animals.

From coral reefs to polar seas, the ocean bursts with life and diversity.

And much of this life is essential to sustaining us. Around the world, more than a billion people rely on fish for their main source of protein, while around 1 in 10 depends on fishing for their livelihood.

We rely on the ocean’s wild bounty so much that fish is the most traded food in the world – above tea, coffee, bananas and sugar.

Oceans at risk

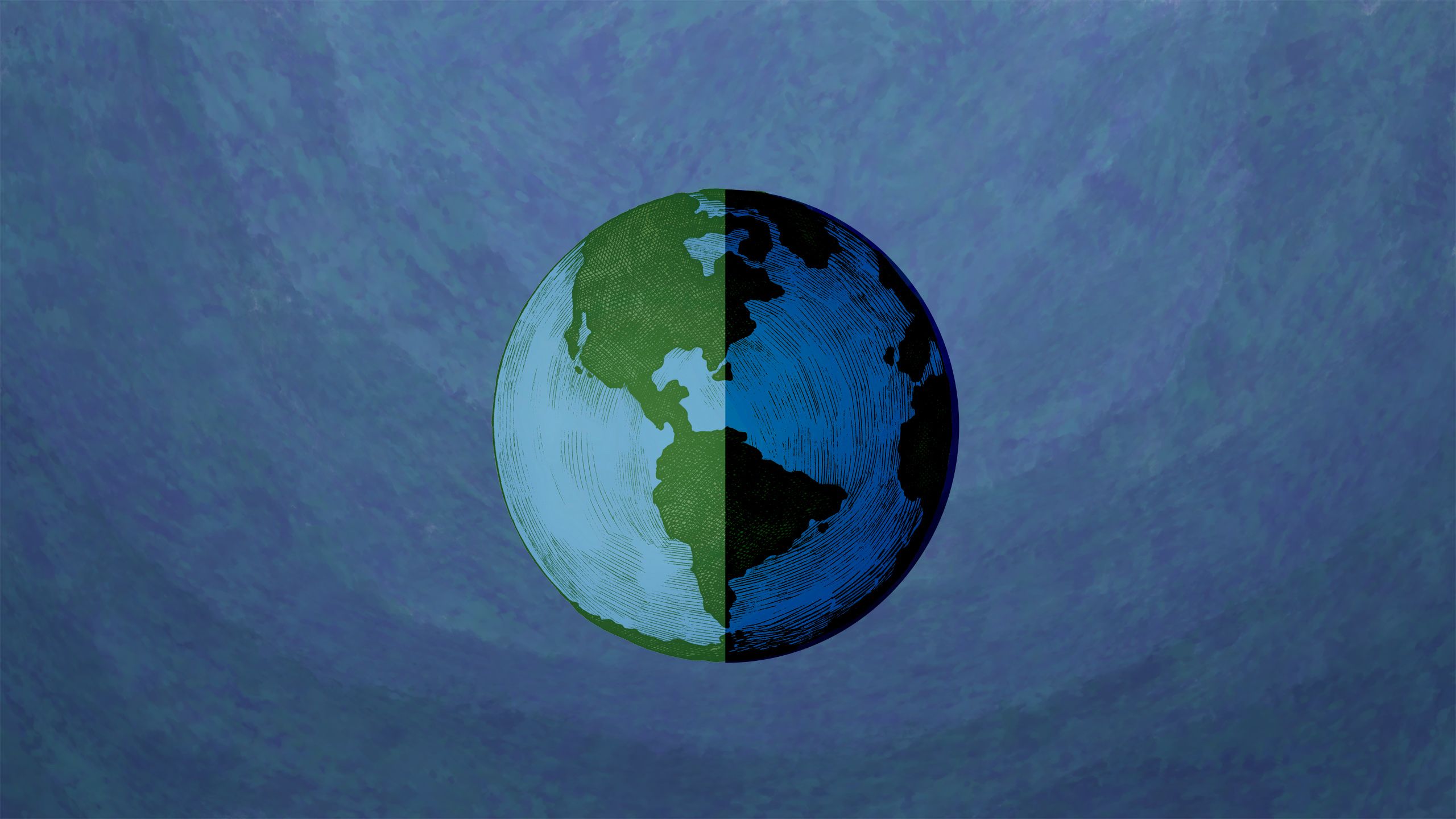

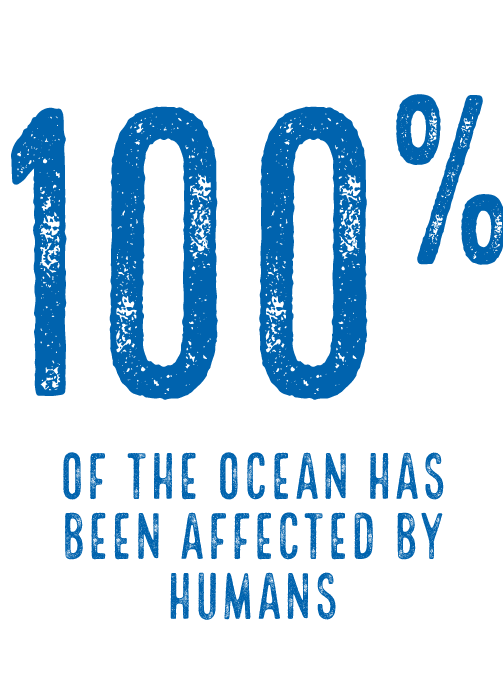

Yet despite this importance, our ocean is in trouble: it’s facing lots of different challenges but three of the key ones are overfishing, illegal fishing, and destructive fishing.

These issues have taken a terrible toll on our ocean, threatening fish stocks and the lives and livelihoods of those who depend on them.

It can be difficult to imagine just how vital fishing is to us. To help you get some idea, take a look at Global Fishing Watch’s interactive online map. It uses cutting-edge technology to track where larger boats catch fish all over the world. The map doesn’t show us everything, because many fishers, especially in developing countries, fish on foot in the shallows, or in boats that are too small to be tracked.

- Go to http://globalfishingwatch.org/map/

- Click the play button in the bottom left hand corner of the screen to see who’s fishing where over time (the blue dots). You can change the dates, zoom in and out, and move around the world to learn more.

- Find somewhere on the coast that you've visited, either in the UK or overseas. How does the fishing pressure there (the number of blue dots over time) compare to the Arctic? Is it higher? Lower? Why might this be?

Why are fish stocks declining?

1 .Losing Nemo

For thousands of years, people have fished in a balanced way where they didn't catch beyond what they needed to eat or sell.

But as global demand for fish has risen, so too has the scale of fishing, and this can lead to declining stocks.

Fishing itself isn’t the problem, as there are fisheries who fish responsibly and sustainably, but without good management, it can be destructive.

When a certain species of fish, usually one people like to eat, is fished too much, the fish are unable to reproduce their numbers back to a healthy level and begin to decline. This is called ‘overfishing’.

Now, almost a third of global fish stocks are overfished.

That’s a lot of fish for us to lose! If nothing is done to prevent this decline, there’s a risk that some species will be gone forever.

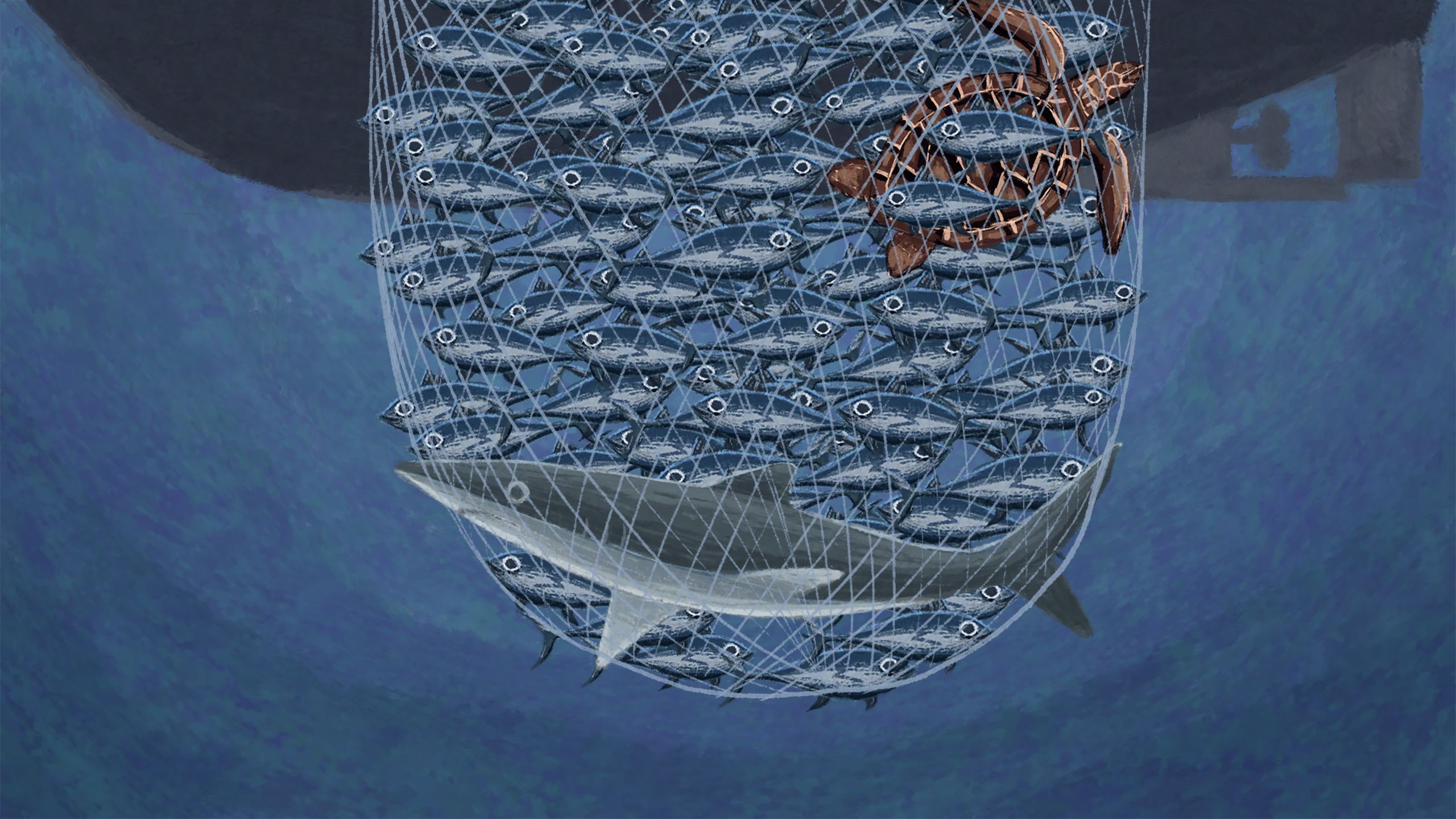

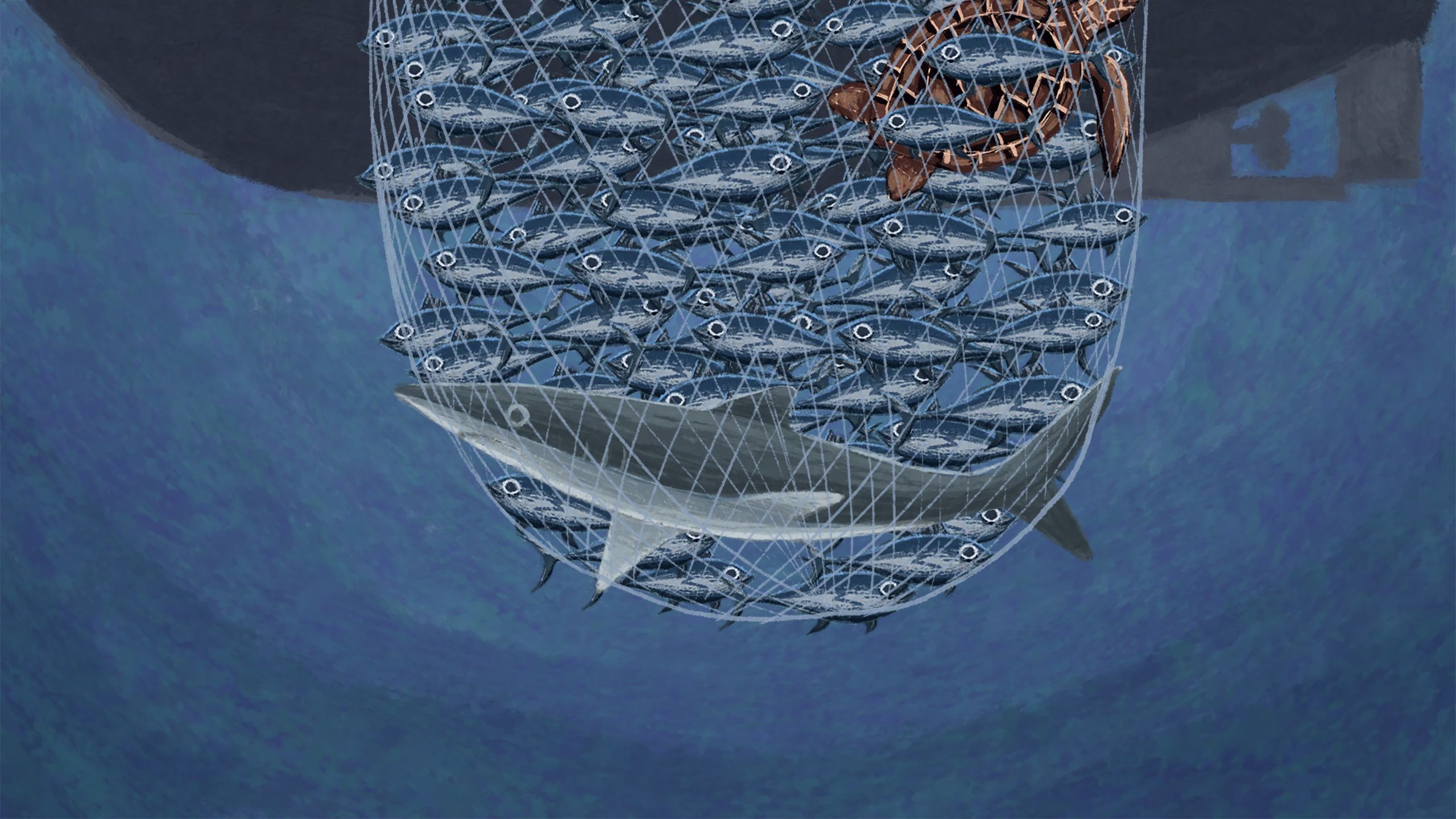

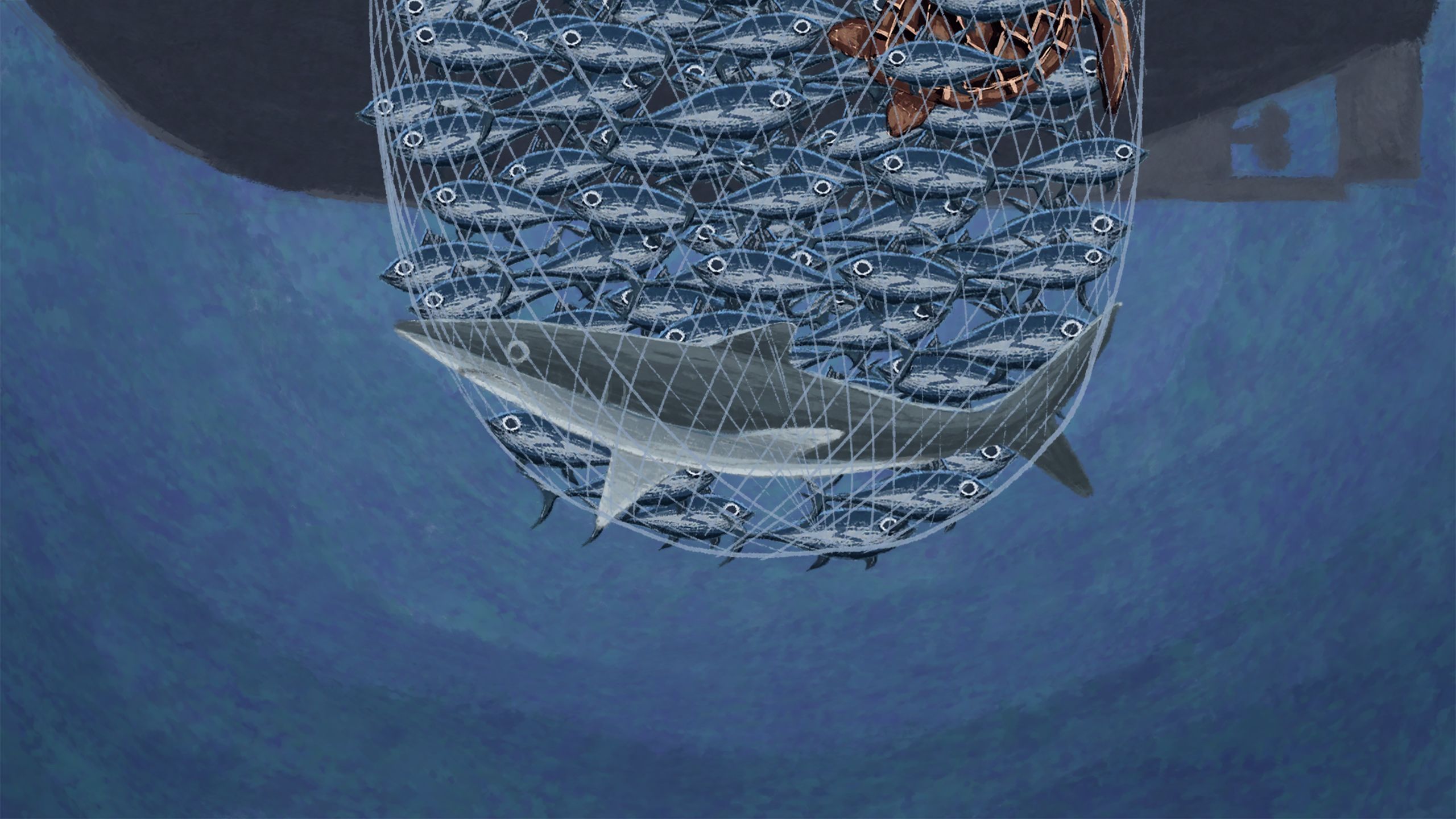

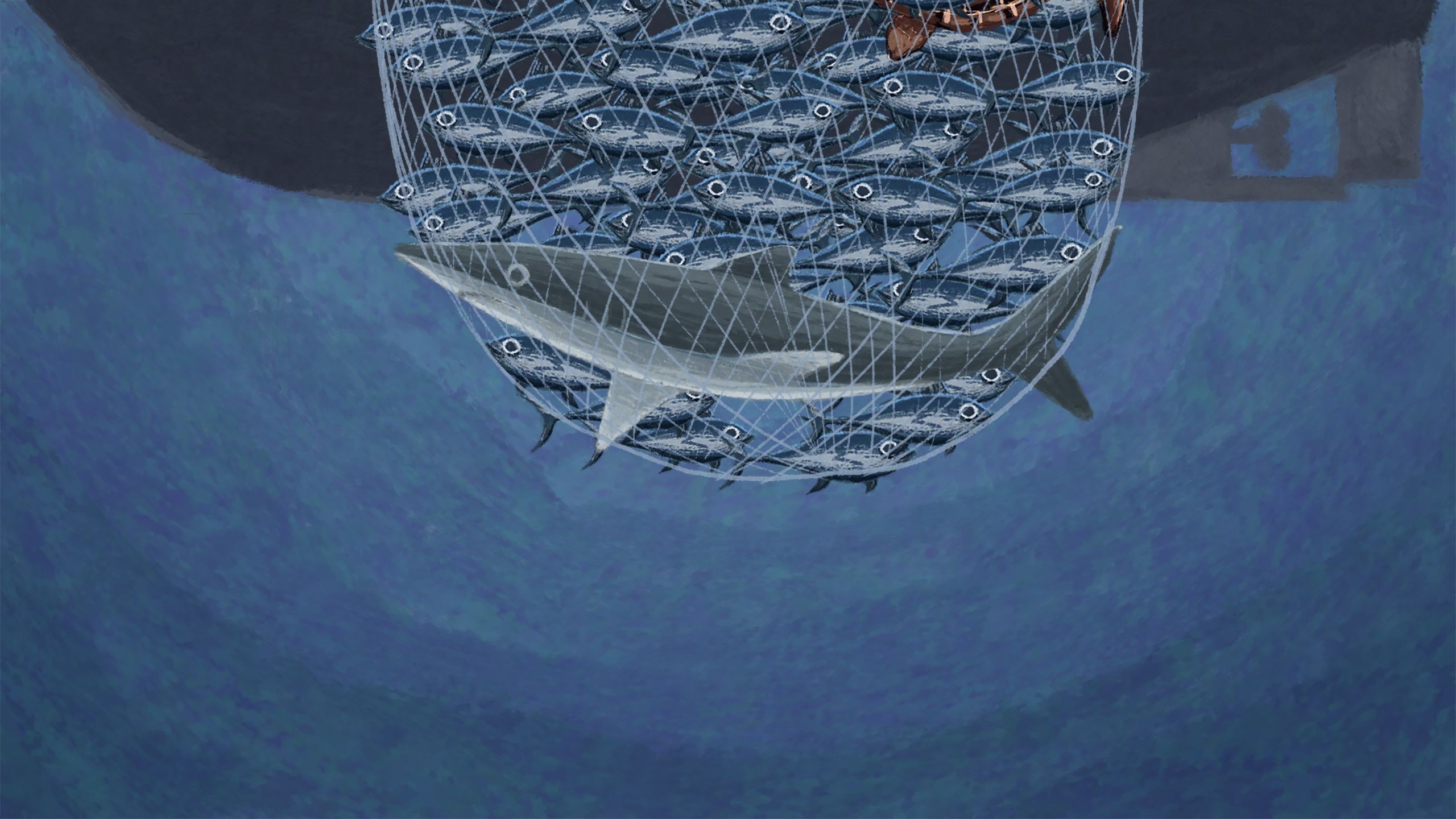

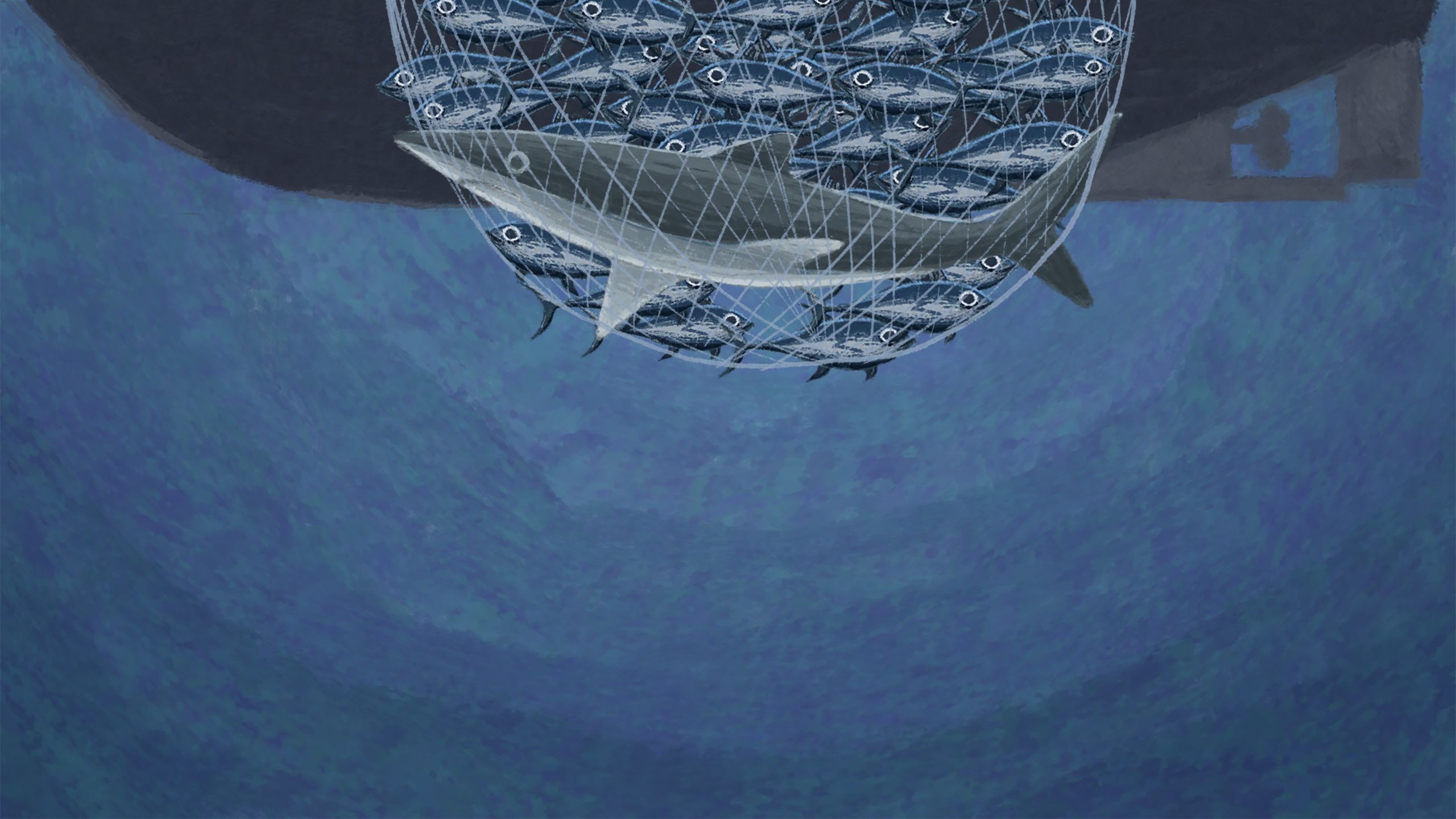

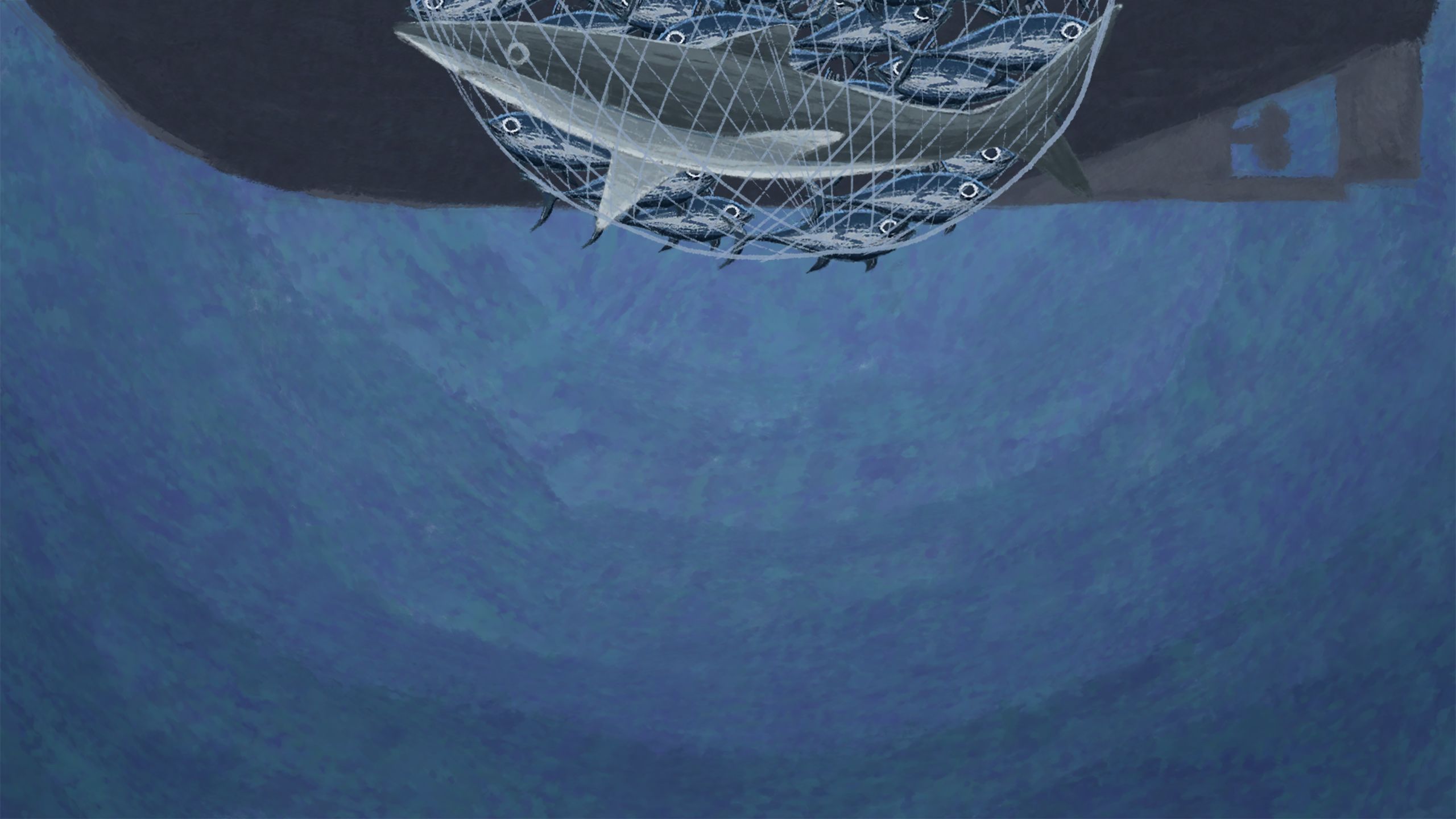

2. Bycatch

Overfishing is not the only reason for this decline. Another problem is ‘bycatch’. Bycatch is when fishing boats accidentally catch fish and animals that they don’t really want, or shouldn’t take. It can be other species of marine life like seabirds and other marine creatures like sharks and turtles.

Bycatch can also include young or undersized fish that are not really big enough to eat so should be left in the sea to grow.

3. Illegal fishing

Illegal fishing is a further threat.

What does this mean?

It usually involves

- Fishing without the proper licenses

- Telling the authorities you caught fewer fish than you actually did

- Catching species you're not allowed to catch

- Taking fish from areas where you're not allowed to fish

- Catching fish using nets or lines that are not allowed

The way that a fish gets from the sea to your plate is complex and not always well known. This means that you and I might be eating illegal fish without even realising it.

Because illegal fishing operates in the shadows, we don’t know what it’s costing us and the ocean.

But some scientists think that up to £18.5 billion of fish are landed illegally each year.

4. Destructive fishing

Some of the places in the ocean where fish breed and live are very fragile and can be damaged by certain ways of fishing. Some of the most destructive fishing practices include cyanide fishing and the use of explosives. Cyanide is used on coral reefs to stun fish, making them easier to catch. For every live fish caught this way, a square metre of reef may be killed.

Explosive fishing involves setting off explosives underwater. This kills the fish, and they float to the surface where they can easily be scooped into waiting nets. Sadly, fishing in this way can completely destroy the underwater environment. In parts of Southeast Asia, dynamite fishing has contributed to the loss of large areas of coral reef.

Look at the two graphs below. Between 1950 and 2016, what happened to global fish production? Did it increase? Decrease? By what percentage? And what has happened to the proportion of global stocks that are overfished, fully fished and underfished? Why do you think this might be?

How can we conserve

fish stocks?

Fishing for the future

I know my dad makes sure he doesn’t over-fish the species he catches and takes care of the marine environment. My dad says he fishes sustainably.

But what does this mean?

Sustainable fishing means leaving enough fish in the ocean, minimising damage to marine life and habitats and ensuring people who depend on fishing can maintain their livelihoods.

To fish sustainably, my dad and other fishers need to know as much as they can about what they catch and the ecosystem it lives in. They find this out by working with scientists to understand how sea life populations change over time, looking at births, deaths and migrations in and out of a given fishery. They use this information to calculate what is known as the “maximum sustainable yield” (MSY) – the number of fish they can catch without overfishing.

MSY is complicated! Click on the image below for a quick explanation.

My dad’s fishery uses this knowledge to catch the right amount of herring, a small silvery fish. Although there are lots of herring in the areas where they fish, they don’t want to catch too many.

That’s partly why his bridge deck looks like a spaceship! All those monitors and panels and gadgets help him to catch the right fish, and the right amount of them. It’s also why he has special nets that allow excess fish to escape via large mesh panels.

If you have a virtual reality viewer* like Google Cardboard, put it on now and take an expedition around my dad’s boat. You’ll get to explore those special nets and that spaceship control room, see below decks, and watch the herring being offloaded when the boat returns to port!

* Don’t worry if you don’t have a special viewer. You can still look around the ship by watching the video with a smartphone and looking at the photos below.

360 virtual reality tour of my dad's fishing boat

Now you've seen how my dad fishes, it's time to discover where he goes to catch his fish. To find this out, we'll be using Global Fishing Watch's interactive online map again.

- Just as you did in exercise one, head over to http://globalfishingwatch.org/map/

- Click on the Vessels menu on the top right of the screen, and type “Immac” into the search box. The site’s name for my dad’s boat is F/V G IMMACULEE, so click on that. The pink tracks show everywhere he’s fished from 2012 right up to last week.

- He took a longer trip in 2018, away from the usual places he fishes. Use the map to find out where he went. Describe his journey in a couple of sentences. Up the coast of which country did he travel, and in which main direction? Using what you learnt from the video, why do you think he might have gone there?

Safeguarding our seas

My dad’s fishery has caught herring in the same way for generations. Because herring don’t swim near the bottom of the ocean, the nets used to catch them can’t easily damage the ecosystem. And because they swim together in dense schools, there’s very little bycatch.

But every fish and fishery are different and many need different interventions to be sustainable. Let's look at a few.

1. Marine protected areas (MPAs)

MPAs are parts of the ocean where certain activities like fishing are restricted or not allowed. They’re known by many other names, including marine reserve and marine conservation zone.

In an MPA, you restrict or stop fishing in an area. After a few years, there are more fish inside this area and they begin to swim across the boundaries into fishing nets outside.

There are more than 14,000 MPAs around the world and scientists know that they can benefit both people and nature through improved fish stocks and larger fish.

But many MPAs don’t protect anything. These areas, which don’t have the funding or management they need to thrive, are known as paper parks.

Despite these issues, MPAs can be an effective way of helping to conserve fish stocks for the future.

Learn how Greenland’s cold water prawn fishery partnered with the Zoological Society of London to protect coldwater corals and sponges in a new MPA

The best way of learning more about MPAs is to visit Protected Planet, an interactive website with lots of information about protected areas all over the world.

- Go to https://www.protectedplanet.net/marine and explore the maps and graphs there

- Where is the world's largest MPA and how big is it? Why might it be harder for an MPA that size to be established in the ocean around the UK?

- What is the Green List and why do you think it might be important?

2. Beating bycatch

All over the world, fisheries like my dad’s are coming up with clever new ideas to reduce bycatch. In Scotland, introducing innovative fishing gear has reduced cod bycatch in the North Sea haddock fishery by 60%. And in Australia, the Western Australia rock lobster fishery reduced deaths from sea lions getting caught up in lobster traps to zero through using exclusion devices.

Read more about how fisheries are reducing bycatch

3. Turning the tide against the illegal fishers

Others are calling time on the pirates that loot our oceans illegally. For many years, Patagonian toothfish was off the menu after pirate fishing decimated stocks. But action by six major toothfish fisheries has all but eliminated IUU fishing in the Southern Ocean. Stocks are rebounding, and toothfish is back on the menu.

Read more about how the pirates were forced to walk the plank

4. Catch shares

In 2001, the once abundant groundfish fishery on the West coast of the USA was on the brink of collapse. The fishers pulled their boats out of the water and came up with a new way of saving their fishery: catch shares.

Catch shares use maximum sustainable yield to work out the right number of fish to catch – the quota. But rather than let every fishing boat catch as much as it wants until the quota is reached, they give each boat a portion of the total catch. This means fishers can harvest their share when they like, or can lease it to others if they are unable to fish.

Discover how catch shares transformed the fortunes of the West coast groundfish fishery

5. Farming our seafood

We don’t just have to catch seafood, we can farm it too. This helps to reduce pressure on wild-caught fisheries and is known as aquaculture. Today, much of the fish we eat around the world comes from aquaculture.

Farming fish responsibly can help to safeguard livelihoods and ensure that people have safe and nutritious food to eat, especially in developing countries. But when it’s not done well, there’s a chance it can harm the environment and wildlife.

Another key problem is that many farmed fish eat other, smaller fish. So aquaculture doesn’t always create new fish, but just converts low value small fish into high value big fish. Scientists want to replace these small fish with alternative food like insects or seaweed, but this is not yet a widespread solution.

Find out more about aquaculture

6. The blue tick

Fishing sustainably is a global challenge that many fishers are tackling. No matter how far away seafood is caught, it ends up in our shops, restaurants and supermarkets for us to buy and eat.

That makes us part of this challenge too. So how do we know which products in the shops are sustainable and which are not?

Along with hundreds of others around the world, my dad’s fishery is certified 'sustainable' by the Marine Stewardship Council.

The MSC is an independent organisation with a standard for sustainable fishing. This standard is used to check whether the fishery is catching fish at a healthy level, that marine life and their habitats aren’t being damaged, and that fish stocks are healthy.

Once all these checks are done, fish and seafood products get a little blue label on so everyone knows.

In a small group or on your own, pick one of the solutions to overfishing you’ve found out about in this section and create an infographic to explain it to the rest of your class.

The links at the bottom of each solution are a great starting point for your research, but you should also try to find out more from other places. You might also want to look at these videos and sites.

What can we all do to make sure our oceans are sustainable?